This post looks at the pattern of merger control decisions during the Competition and Markets Authority’s (CMA’s) second full year, which ended on March 31st. The decisions covered are those for which final decisions were published during the year.

In summary:

2015/16 turns out to have been a record-breaking year in many different respects

- A record low number of Phase 1 merger decisions

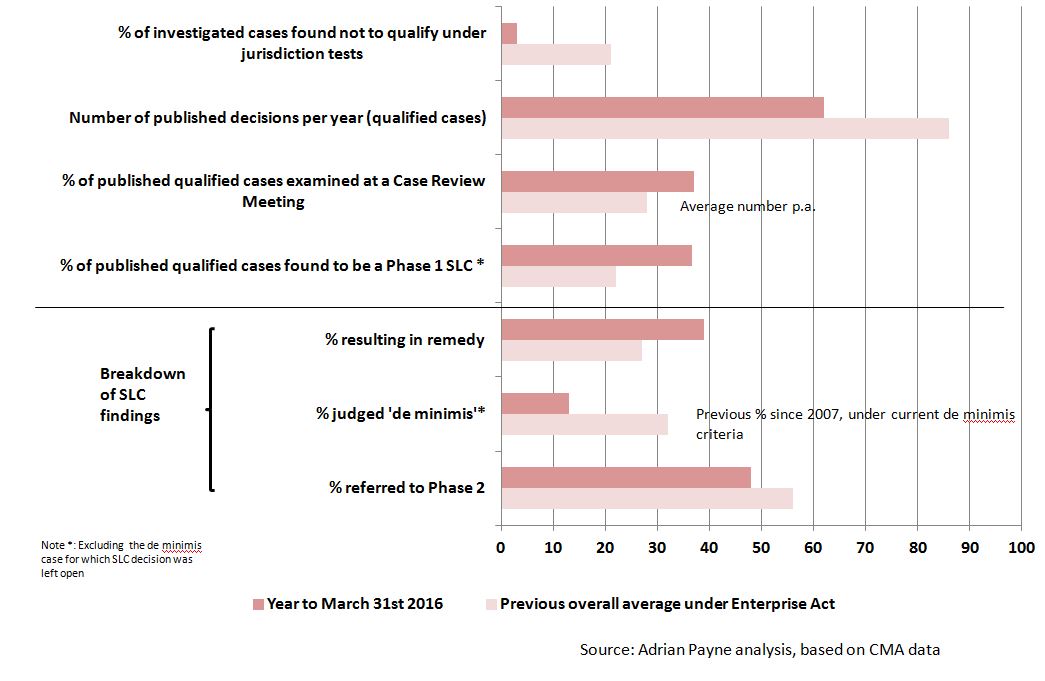

The 62 published CMA Phase 1 decisions was the lowest number of any year since the Enterprise Act came into force and well down on 2015/16.

A third successive sharp drop in the number of non-notified mergers that the CMA ‘called in’ for investigation contributed to the fall. Only 10 cases were called in, the lowest number I can recall for any year. Another record.

Phase 1 Merger Decisions – 2015/16 compared to previous years

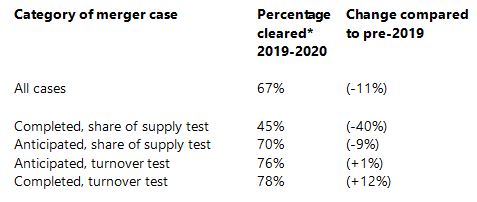

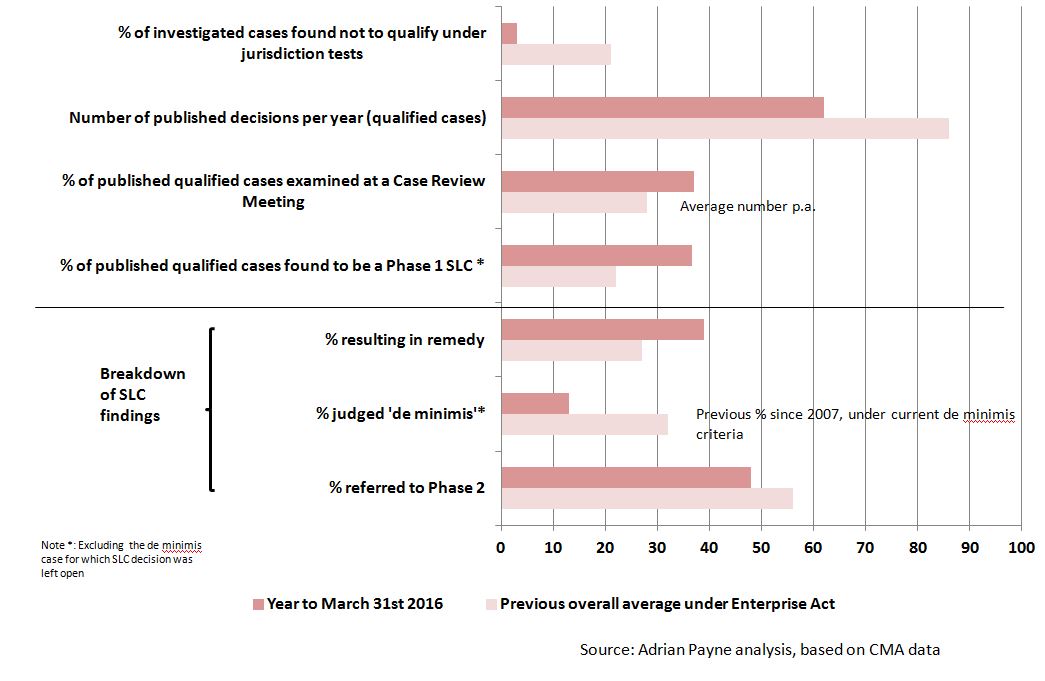

2. A record low number of decisions was found not to meet the jurisdiction criteria

The number and proportion of published cases found not to meet the qualifying tests for jurisdiction was in 2015/16 a fraction of its historic average – and by far the lowest in any year so far under the Enterprise Act.

3. Phase 1 competition problems at a record high

The proportion of Phase 1 cases meeting the jurisdiction tests (so-called ‘qualified cases’) that was found to threaten a ‘substantial lessening of competition’ (SLC) doubled compared to the CMA’s first year and reached a record high of 38%.

There are two elements to this that are worth noting:

- Cases that are candidates for a Phase 1 SLC decision are examined in detail at a so-called ‘Case Review Meeting’, late in the Phase 1 process. The proportion of cases taken to a Case Review Meeting was well above average in 2015/16.

- And of those cases, over 80% resulted in an SLC finding – again well above average.

- The lowest ever proportion of cases decided at Phase 1

The proportion of qualified cases decided at Phase 1 was the lowest to date under the Enterprise Act.

This result stems from the fact that, even though the proportion of problematic cases referred to Phase 2 for further investigation was well below average, the percentage of problematic cases in the overall caseload was at a record high, as described above.

- The proportion of problematic Phase 1 cases deemed too small to merit a Phase 2 investigation was at a record low

This statistic relates to so-called ‘de minimis’ cases. It is a great example of how one needs to look at individual cases (both notified and un-notified) in order to interpret the result.

Might it indicate that the CMA is taking a harder line on arguments put to it that a case is too small to warrant further investigation? Or does it show that the CMA is calling in fewer potential ‘de minimis’ cases? Cases strongly favour the latter.

6. A record high for Phase 1 remedies

The proportion of problematic cases dealt with by remedies at Phase 1 rose to a record high of nearly 40% in 2015/16.

It is striking that, at one point during the year, seven out of ten consecutive SLC decisions (excluding de minimis cases and automatic references) were dealt with through Phase 1 remedy rather than reference to Phase 2, another record under the Enterprise Act as far as I recall.

It is interesting that this is in the context of there being….

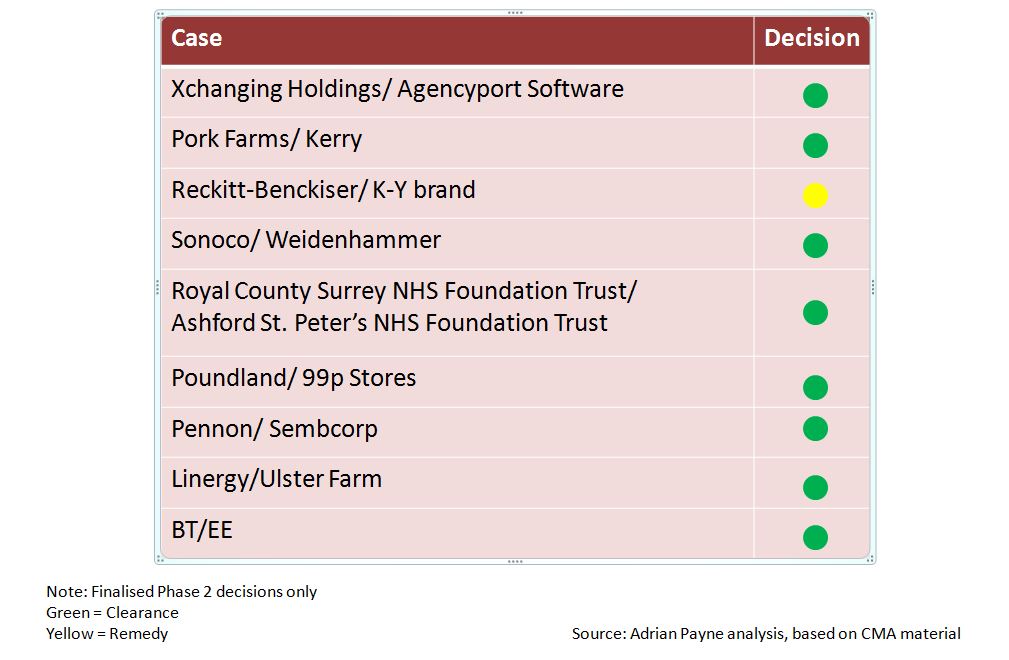

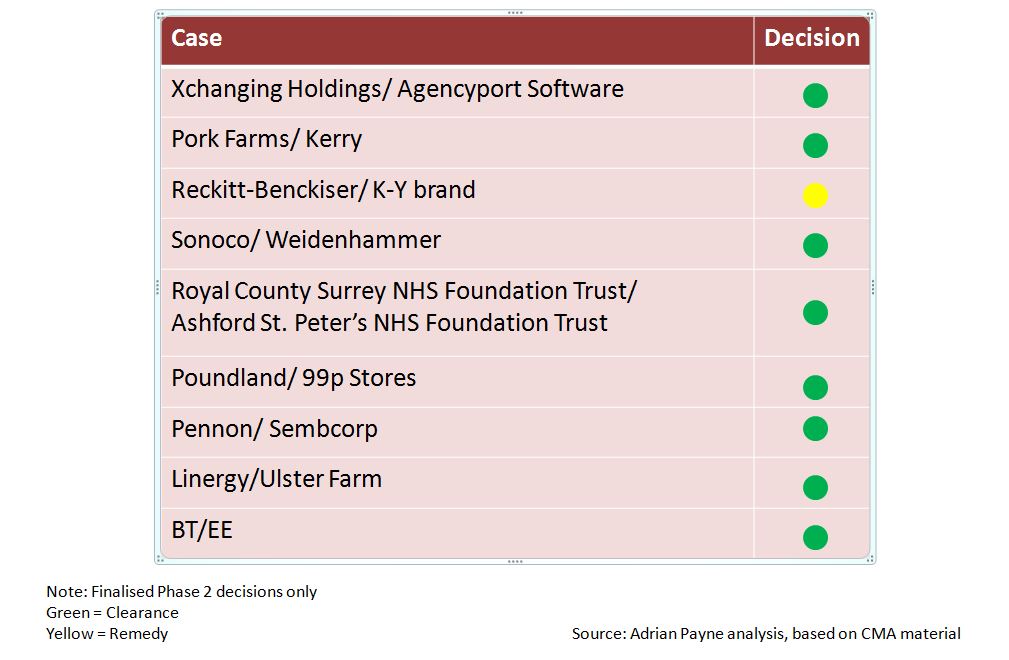

7. No Phase 2 prohibitions for the second consecutive year.

This means that the CMA Phase 2 decision-makers have yet to prohibit a merger.

There have, however, been two previous occasions in which there have been no prohibited mergers for two consecutive years. So this one isn’t a record !

2015/16 – CMA Final Phase 2 Merger Decisions

Looking ahead

Where does this cascade of new merger records leave the CMA, merging firms, competitors and customers?

There is little doubt that the CMA has become increasingly selective in the cases it has chosen to call in for investigation, to a degree that requires highly reliable information being available from merging parties in order to enable the CMA to avoid missing too many problematic deals of reasonable size.

The particular challenge here for the CMA is to make these ‘call in’ decisions accurately and quickly outside of the formal review process, without the range and quality of cross-checks that comes from interaction with competitors and customers when a case is called in for review.

As some have already recognised, for merging parties greater CMA selectivity is clearly relevant to decisions regarding notification. A key question, therefore, is whether the CMA will decide to be as selective in the year ahead. It is worth remembering here that there has already been more than one occasion under the Enterprise Act when tighter case selection has been followed by a move back to a more expansive approach to calling in cases for review.

For customers and competitors greater CMA case selectivity clearly puts a premium on making representations more quickly, rather than waiting for a formal investigation to begin. The much-expanded role for pre-notification also points in this direction, as does the earlier involvement of the Phase 1 decision-maker than used to be the case.

Turning to substantive decisions made during 2015/16 , as the National Audit Office recently put it, “the CMA is expanding the practice of clearing cases with remedies in phase 1 without the need to go for a more detailed and resource-intensive phase 2 review.”

It would be easy, however, to overstate the extent to which the 2015/16 remedies record is due to the CMA’s expanded Phase 1 remedy ambitions. In particular, the increasing level of challenge in many deal valuations (a factor in the low number of deals) seems to me to have had a notable effect on the appetite for regulatory risk and therefore the pattern of deals being brought to fruition (including their suitability for Phase 1 remedies).

Two other questions are also relevant here:

- To what extent has the way in which CMA plans and manages its casework (now that Phase 1 and Phase 2 are under one roof) affected the pattern of Phase 1 decisions being made?

- And what has been the impact of certain ‘bold’ Phase 2 clearance decisions on the attitude to remedies at Phase 1, both by parties and by the CMA?

On the whole, my own 2015/16 casework leads me strongly to suspect that the CMA’s record-breaking year for mergers hides patterns that are more complicated than they first appear from the aggregate statistics.

As always, many of the main lessons for interested parties to future mergers come from understanding what has worked well or badly in individual cases during 2015/16, as well as from understanding what the aggregate figures do and do not show.

In both respects 2015/16 should leave plenty of pause for thought for all concerned.

——————————————————-

© Adrian Payne, 2016